Alaska Glacier Directory

The Ice Age hasn’t ended in Alaska! Gobs of hanging glaciers can be seen from just about every highway that traverses Alaska’s high mountains. Many terrestrial glaciers can be approached up close by people who can handle short hikes. Go to sea on a day cruise or fishing charter, and you’ll discover the coastal mountains of Southcentral and Southeast Alaska are among the best places in the world to experience glacier calving. And don’t forget the uncounted thousands in remote areas—many accessible by air charters or mountaineering trips. You’ll never run out of glacial viewing options.

Jump To | Map | By Road or Rail | Hike, Bike or Ski | Boat Cruises | Flightseeing & Glacial Landings

By Road or Rail

Matanuska Glacier

About 100 miles northeast of Anchorage

Located at the end of a private road through a resort at Mile 102 of the Glenn Highway—about 50 miles east of Palmer—this craggy, heavily crevassed river of ice is the real thing. It’s fed by the same ocean-driven weather that creates the vast glacial crown surrounding Prince William Sound. And it can be touched!

Portage Glacier

About 50 miles southeast of Anchorage

This very active glacier now hidden inside a lobe of Portage Lake has undergone what may be the most closely watched retreat of any glacier in Alaska. Decades after it exposed its own deep lake, the Begich, Boggs Visitor Center was built specifically to showcase a stunning head-on view of its rugged, collapsing face. Though the glacier finally slipped from easy view in the 1990s and became largely a tour boat destination in summer, Portage continues to generate icebergs that ground within sight of lakeshore parking.

Spencer Glacier

About 10 miles south of Turnagain Arm on the Alaska Railroad

For a unique, European-style excursion that offers direct access to an active glacier that clogs its lake with amazing icebergs, take a train to the Spencer Glacier Whistlestop station during the summer visiting season. Guides offer activities such as sea kayaking and rafting, hiking and climbing. The U.S. Forest Service maintains a campground (reservations required.) You can backpack a new trail system, rent a public use cabin on a mountain ridge, or explore a basin recently emerging from beneath ice.

Exit Glacier

About 12 miles outside Seward on a paved road

This dramatic tongue of ice descends from the massive Harding Ice Field to a visitor center with curated trail system, located inside the only portion of Kenai Fjords National Park reachable by road. Signage identifies the glacier’s terminal locations during its retreat over the decades, making the access trail a real-time index into the dynamics of climate warming. The easy lower trail leads to overlooks of crevasses.

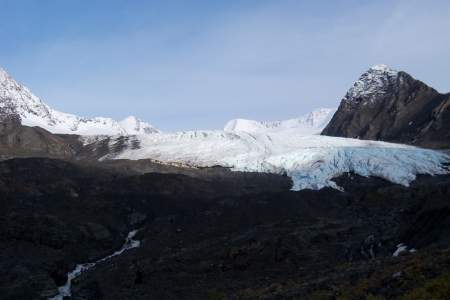

Worthington Glacier

About 29 miles north of Valdez on the Richardson Highway

One of the most popular natural attractions on the Valdez-to-Fairbanks highway corridor, this active glacier descends almost to the Richardson Highway, and can be easily approached via a short trail system. Great photographic potential during summer, with picnicking, wild blueberries and restrooms.

Mendenhall Glacier

Mendenhall Glacier

About 12 miles from downtown Juneau

This 13-mile-long river of ice descends from the immense Juneau Icefield into a berg-strewn lake only minutes from downtown Juneau. It is the easiest glacier to visit in Southeast Alaska, and one of the most popular glaciers in the state. A visitor center operated by the U.S. Forest Service is open year-round with spectacular views and interactive exhibits, plus you’ll find great hiking to waterfalls and overlooks for photography.

Childs Glacier

About 50 miles from Cordova at the end of the Copper River Highway

The terminus of this active glacier looms over the main channel of the Copper River just across from a popular campground. Calving events sometimes throw 10-foot waves that strand flopping salmon on the forest floor. The historic Million Dollar Bridge—damaged in the Great Alaska Earthquake of 1964—is nearby. Unfortunately, a washed-out bridge on the road to the glacier currently complicates access.

Highway Shoulders During Road Trips

Look up, and you shall see. After seasonal snow recedes during spring and summer, scores of glaciers become readily visible on slopes overlooking highways that traverse Alaska’s coastal mountains and the Alaska Range. Generally, by the time you can see green vegetation in the chutes and bowls near ridge tops, most of the white, icy masses on looming slopes will be bona-fide hanging glaciers rather than just late-melting snow. Most have no names. Enjoy them as you travel!

Promising stretches include:

- Seward Highway southeast of Bird Point and north of Ingram Creek. Watch for glaciers overlooking Girdwood and Alyeska Resort. Look for the many sparkling buttresses that cling to the mountains above the Portage and Placer river valleys at the head of Turnagain Arm.

- The Alaska Range seen from the Parks and Richardson highways. A great way to start would be to visit the best Denali viewing sites. The waysides at Parks Mile 135 and Mile 163 inside Denali State Park are prime. On the Richardson, watch for glacier views during a 50-mile stretch between the Summit Lake area north of Paxson through Donnely Lake. Good views of the Gulkana Glacier can be found in a primitive camping area about 1.5 miles up an access road to a former pipeline construction camp, running east about two miles north of Summit Lake.

- The Chugach Mountains along the Glenn Highway between Glacier View area and Eureka Summit. Glaciers will be nestled in hanging valleys and in distant drainages. The most extraordinary ice vista will be at the Matanuska Glacier State Recreation Site at Mile 101. Find views of the distant Tazlina and Nelchina glaciers to the south in the Eureka Summit area around Mile 129-Mile 132.

Hike, Bike or Ski

Byron Glacier

About 50 miles southeast of Anchorage

Only a short hike on a flat trail south of Portage Lake near the head of Turnagain Arm, Byron dominates its own gorge-like valley, offering a rugged, remote atmosphere that feels as though you’ve traveled deep into the backcountry. It also hosts a population of ice worms.

Portage Glacier

About 50 miles southeast of Anchorage

Listed above as a road accessible, Portage Glacier can be approached under human power via the Portage Pass Trail from the Whittier side of the Anton Anderson Memorial Tunnel. Non-motorized boats like kayaks are permitted along the north shore of Portage Lake to the beach at the base of Portage Pass, with a great view of the ice. During winter—once Portage Lake freezes solid—people also walk, ski, ice skate and snow bike about three miles to the vicinity of the glacier’s active face.

Root Glacier

About 300 miles east of Anchorage in Wrangell St. Elias National Park

For those able to handle a four-mile round-trip hike with a couple of moderately steep sections, an obvious trail from the historic Kennecott town site leads north to the Root Glacier. On a sunny day, the photography is outstanding, in a locale that’s as wild and exotic as it gets.

Kennicott Glacier

About 300 miles east of Anchorage in Wrangell St. Elias National Park

The spectacular Kennicott Glacier dominates the vista from the historic copper mill town of Kennecott and the decks of the Kennicott Glacier Lodge, 4.5 miles from the end of the McCarthy Road inside Wrangell St. Elias National Park. Shuttles regularly operate between McCarthy and Kennecott.

Eklutna Glacier

About 40 miles from downtown Anchorage inside Chugach State Park

A landmark at the head of a multi-use trail inside Chugach State Park, this fast-receding glacier anchors one end of a popular mountaineering traverse that connects to the Girdwood area on the other side of the range. Depending upon the time of year and snow cover, Eklutna’s toe can be quite treacherous (but beautiful) with headwalls, rock slides and fins of ice. The narrow gorge has the raw, wild feel of a defile far from civilization.

Raven Glacier

Near Crow Pass about 8 miles from Girdwood

This stranded mountain glacier sprawls from its hanging valley below Crow Pass—a white, striated mass with blue-etched crevasses. If approached after the snow has melted—late June through September—the contrast between the glacier and the surrounding tundra, gravel and rock is startling and otherworldly. Considered one of Alaska’s best summer day hikes.

Day cruise in Whittier

Mint Glacier

About 60 miles north of Anchorage in the Hatcher Pass area

The very doable 8-mile Gold Mint Trail in the Hatcher Pass area north of Palmer parallels the Little Susitna River up a gorgeous valley to its headwaters and a ridge overlooking Mint Glacier. The total elevation gain is about 3,000 feet, but the trail is mostly gradual and popular for backpackers and day-hikers, especially from July until snowfall.

Day Cruises to Tidewater Glaciers

There’s nothing else like the moment a giant hunk of ice calves from the face of a glacier and then crashes into the sea. This display of immense natural violence fills the senses. There’s the groan of tortured ice, the artillery-shot crack as it shatters, the rumble of its collapse—all ending in a colossal splash followed by tsunami-like waves that jostle floating ice and bergs and maybe rock your boat. Alaska may be the best place in the world to witness this spectacular phenomena. Most people book a day-trip on a marine tour.

Whittier

About 60 miles from Anchorage

Many tour companies and small-boat operators offer daily excursions into Western Prince William Sound from this port town on the road system about 60 miles from Anchorage. Popular destinations with a good chance of witnessing calving include Beliot and Blackstone glaciers at the head of Blackstone Bay and the very active Surprise Glacier in Harriman Fiord.

Valdez

At the head of Valdez Arm in Prince William Sound

Known for the terminal of the Trans-Alaska Pipeline and colossal winter snowfall that can literally bury housing, this friendly port town at the end of the Richardson Highway is one of Southcentral Alaska’s best launch spots for glacier touring. Guides and marine tour operators offer trips to the Valdez Glacier near town, the Shoup Glacier further out Valdez Arm, and to the immense Columbia Glacier—now undergoing drastic retreat and exposing a new spectacular fiord.

Gustavus (Glacier Bay National Park)

44 miles west of Juneau

Gustavus is the gateway to Glacier Bay National Park, the most stunning place in Alaska to witness a fiord system newly exposed by retreating ice. The park features seven tidewater glaciers that actively shed icebergs and brash into 65-mile deep bay that didn’t yet exist in the 1700s. For sheer rugged wilderness character in an ecosystem that’s fast exiting the ice age, there’s nothing else like it. Though most people visit Glacier Bay on cruise ships, there are many other tour options once you get to Gustavus.

Flightseeing and Glacial Landings

One of the most spectacular and otherworldly modes to view glaciers is from the air. What might appear as a static (but enormous) landform from the ground or the deck of a boat suddenly seems to come alive in real time, like you’re rocketing down an undulating river as it twists through canyons and plunges over falls. Only from the air do you fully perceive how glaciers are flowing downhill in slo-mo, in some ways resembling gigantic lava floes. As they spill from accumulation zones through gorges and valleys, you follow the curves where crevasses rip open and track the serpentine lines of rocky lateral moraines that stripe their spines. Flightseeing transforms glacier viewing into something like the grandest amusement park ride you’ve ever imagined.

Alaska hosts an entire industry that specializes in flying visitors into glacier country, ranging from hour-long overflights to extensive trips that might involve landing or drop-offs on active ice. There are scores of carriers in dozens of communities, using both ski-equipped airplanes and helicopters. While many visitors aspire to visit the extraordinary icebound realms like Ruth Glacier in Denali or the Kennicott and Root glaciers of Wrangell-St. Elias national parks, don’t count out the less remote backcountry of the Chugach, Kenai and Talkeetna mountains. Many air charters take off from Merrill Field and Lake Hood airstrips right inside Anchorage.

For More Information:

Show Map

Glaciers by Access

Roadside Glaciers

This 12-mile glacier is part of Tongass National Forest and its visitors’ center is just a half mile from the glacier’s face. Once dubbed the Auk Glacier by John Muir (after a member of the Tlingit tribe),

This very active glacier forms a wall along the fabled Copper River near a historic railroad route that once serviced the world’s largest copper mine. NOTE: A bridge at Mile 36 of the Copper River Highway is currently (2020) impassable, with repairs not expected for several years. Child’s Glacier is not currently accessible by road. Contact Cordova Ranger District for current venders providing transportation options to the far side. ...more

You can hike right up to Seward’s Exit Glacier and feel the dense blue ice while listening to it crackle. Walk the lower trail to get a good photo in front of the glacier face. Or, choose the more challenging 7‑mile round-trip Harding Icefield Trail. There is a short ranger-led walk daily at 11am and 3pm, from Memorial Day through Labor Day.

Some 15,000 years ago, this glacier reached another 50 miles west to the Palmer area. It now has a four-mile wide towering face that you can walk right up to and touch. Keep an eye out for summertime ice-climbers at this most impressive roadside glacier. Directions: Head north from Anchorage on the Glenn Highway. At mile 102, you can drive down to Glacier Park (888−253−4480), then hike 15 – 20 minutes to the face of glacier.Distance: 102 miles ...more

This short day hike — with an easily accessible trailhead a few hundred meters from the Begich Boggs Visitor Center — offers you big views of the Byron Glacier.

One of the most visited natural attractions along the Richardson Highway, this four-mile-long glacier descends almost to pavement and is easy to approach on foot. The state recreation site features parking, pit toilets, and a covered pavilion with a model of the glacier and interpretive signs, all close to small lake.

These gleaming valley glaciers perch in the mountains above Portage Valley, easy to view from highway pullouts. They feed the nearby stream systems that harbor many species of salmon and trout. Tangle Pond and Tangle Creek are favorite fishing spots for locals, and there are lots of places to camp in Portage Valley itself.

Trailside Glaciers

13-mile glacier in the Kenai Mountains.

This white ribbon of ice merges with the much larger Kennicott Glacier only a mile or so northwest of the historic mill town of Kennecott in Wrangell St. Elias National Park. One of the most accessible glaciers in Alaska, it can be reached by hiking a few miles up a relatively easy trail.

The 700-square-mile Harding Icefield, one of four major ice caps in the United States, crowns Kenai Fjords National Park. The icefield may be a remnant of the Pleistocene ice masses once covering half of Alaska. The magnificent coastline of Kenai Fjords is steep valleys that were carved by glaciers in retreat. Active glaciers still calve and crash into the sea as visitors watch from tour boats here. Sea stacks, islets, and tagged shoreline… ...more

This glacier dominates all views west of the historic mill town site of Kennecott (basically located “across the street” from the Kennicott Glacier Lodge) in the heart of Wrangell-St. Elias National Park. Although Kennicott Glacier has been receding from its terminus for years, its immensity and ruggedness remains a magnificent sight, filling the four-mile-wide valley like a mighty river.

You can find a great overlook that shows off most of the glacier near the 3,880-foot Crow Pass, about three miles from the Crow Pass trailhead in Girdwood. Another mile past the pass, and you can approach the edges or toe of the glacier itself, for a more intimate experience of its texture, colors and gnarled shape.

Located in Wrangell-St. Elias National Park, this 4.4‑mile trail takes hikers through a rugged landscape of ice, rock, and streams. It’s a moderately challenging hike that offers stunning views of the glacier and surrounding mountains.

Located in the Hatcher Pass area of the Talkeetna Mountains northwest of Palmer, the Mint Glacier area is a popular day-hike, summer backpacking and ski mountaineering destination. Intermittent views of the glacier from the Gold Mint Trail will only get better the further you hike up the valley.

To see the glacier, you have to travel into the gorge, a 26-mile round-trip from the trailhead over a mostly flat multi-use trail. (It opens to ATV use on certain days.) Once you enter the canyon, you will see the rugged, boulder-choked terminus with fluted ice above. This somewhat strenuous day-trip over a gravel ATV route takes you deep into the backcountry in just a few hours, with great photography and a chance to see the ravages of climate ...more

Boatside Glaciers

Gorgeous Portage Glacier lies just 48 miles south of Anchorage. Explore the glacier, visit the museum, and go for a boat ride.

Grand Pacific Glacier can actually be found in two countries. Part of the tidewater glacier is located in Reid Inlet within Glacier Bay National Park in Alaska, while the other side can be found in the Grand Pacific Pass in British Columbia, Canada. Back in the 1700s, Grand Pacific Glacier filled the entire bay, and reached all they way to the Icy Strait.

Gorgeous tidewater glacier.

Naturalist and author John Muir first made his way to Alaska in 1879, where he went to explore Glacier Bay. Later, a valley glacier in Glacier Bay National Park was named after him. Just under 90 miles from Juneau, Muir Glacier was a popular stop for many tourists in the late 19th century, and still is today. Be sure to catch Muir on your cruise through Glacier Bay!

From May to late August, you may see loons, mergansers, golden eyes, and arctic terns flying through here on their migration routes. This is also a good vantage point to look back up Barry and Coxe Glacier.

Named after Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland, this is one of Alaska’s most picturesque glaciers. It’s 12 miles long, located in Glacier Bay National Park and has been confirmed to be one of few glaciers that is still advancing rather than shrinking. The only access to the face of the glacier is by cruising up the Johns Hopkins Inlet.

The 2000 photograph documents the continuing advance of Harvard Glacier, which has completely obscured the view of Radcliff Glacier. Baltimore Glacier has continued to retreat and thin. Alder has become established on the hill slopes, but is difficult to see from the photo location. Harvard Glacier has advanced more than 1.25 kilometers (0.78 miles) since 1909. (USGS Photograph by Bruce F. Molnia).

Lamplugh is about 96 miles northwest of Juneau, and is often a stop on cruises going through Glacier Bay National Park. If you’re wanting a more adventurous visit, go sea kayaking in Glacier Bay and make Lamplugh Glacier a stop on your route.

The last two aerial photographs in this group of five document changes that occurred during the 69 years between June 1937 and July 28, 2006. Both photographs are taken towards the north and show the retreating, calving, tidewater terminus of Yale Glacier, located at the head of Yale Arm, College Fiord, Prince William Sound, Alaska. In 1937, Yale Glacier’s terminus was located at about the same position that it occupied when it was visited by… ...more

One of few glaciers that are actually advancing, Margerie Glacier is about 21 miles long and 250 feet high (with a base 100 feet below sea level). The tidewater glacier has been growing roughly 30 feet per year for the last few decades, and has joined and separated from Grand Pacific Glacier over the past twenty-five years.

This is the most active tidewater glacier in Prince William Sound and the best place to see glaciers calving. Surprise also seems to create its own weather; it can be clear around here even when it’s cloudy everywhere else in the area.

Aialik Glacier is the largest glacier in Aialik Bay, located in Kenai Fjords National Park. While fairly stable, the glacier calves most actively in May and June. The glacier is very accessible on a kayak tour or day cruise from Seward.

The famous surveyor Mendenhall named this glacier for a miner who was carrying mail from Cook Inlet to Whittier in 1896, disappeared in a snowstorm, and was never seen again. His brother Willard (who gives his name to the nearby island) searched for him but found only the mail packet atop the glacier which now bears his name.

In this series of photos from June of 2002, Bruce Molnia of the USGS documented the advancing terminus of Hubbard Glacier and the channel cut into the top of its push moraine that blocked the mouth of Russell Fiord. A push moraine is sediment that, in this case, has been bulldozed from the floor of Russell Fiord by the advancing ice. In a few views, some of this sediment can be seen in contact with the bedrock on the wall of the fjord.

Columbia glacier is located in Prince William Sound. At over 550 meters thick at some points and covering an area of 400 square miles, this glacier is a sight to behold, whether from a boat or the sky. It snakes its way 32 miles through the Chugach Mountains before dumping into the Columbia Bay, about 40 miles by boat from Valdez.

Holgate Glacier, found in Holgate Arm in Aialik Bay, within Kenai Fjords National Park, is a tidewater and mountain glacier. While it is one of the smaller glaciers in Aialik Bay, Holgate Glacier is still a popular destination to see calving glaciers. And it is actually advancing! Holgate Arm is often filled with ice, but on a good day you can get to a close and safe distance from the glacier. Catch a cruise from Seward, or go kayaking!

Like its name implies, Cascade twists steeply down a mountainside into the west side of Barry Arm. The dividing line between Cascade and Barry Glacier is sometimes hard to distinguish, because they converge into each other. Cascade is in rapid retreat. The large rock behind the kayaker in this photo was under ice only five years ago. Today, the rock is not only exposed, but the glacier has pulled back away from it another several hundred feet. ...more

This glacier, named after Northwestern University in 1909, can be found at the head of Northwestern Fjord in Kenai Fjords National Park, just under 30 miles southwest of Seward. By the second half of the 20th century, Northwestern Glacier’s recession revealed a number of islands in the Fjord that had previously been covered in ice. Take a cruise from Seward and envision the entirety of of Northwestern Fjord filled with ice, as you make your way ...more

20 miles west of Valdez, this short glacier features a very steep dropoff from ice to ocean!

The Knik Glacier snakes out of the Chugach Mountains, tumbling into an iceberg-studded lake that feeds the Knik River. Experience the glacier up close on an ATV tour from Palmer, or a flightseeing trip (with optional landings on or near the glacier) from Anchorage or Palmer. Flights are as short as 90 minutes round-trip, making it one of the most accessible and impressive glaciers from Anchorage.

Carroll Glacier, found in Glacier Bay, is a terrestrial glacier. Although it receded throughout much of the twentieth century, Carroll Glacier experienced a surge in the 1980s.

Barry Glacier actually flows behind College Fjord and parallel to it for a dozen miles before plunging into the head of Barry Arm. On many days, it spawns enough ice into the Arm to prevent boats from getting close. It all depends on the tide, winds, and calving activity. Sometimes, a bay clear of ice can fill up in less than an hour.

A few hundred feet above the boat, you’ll see Northland Glacier perched atop sheer rock. This glacier calves a lot. The ice blocks ricochet and shatter down the rock face before exploding into the water below. It’s an exciting spectacle. Also, a steady waterfall drains down; to the side, you’ll see a kittiwake rookery.

Beloit Glacier fluctuates betwen 125 and 250 feet high at water’s edge depending on recent calving activity. Calving diminishes the face but it builds back up again quickly as the glacier descends to sea. Nonetheless, the glacier is in rapid retreat; you can spot bedrock becoming exposed at the base of the glacier. It was named after the Wisconsin college, as were most of the other glaciers in Blackstone Bay (Lawrence, Marquette, Concordia,… ...more

Coxe Glacier forms a dramatic and noisy backdrop to Black Sand Beach. It’s not as active as either Cascade or Barry, but it packs enough punch to awaken even the deepest sleeper when it cracks and thunders just a quarter mile away from camp. There are several decent campsites with head-on views of the glacier.

Look down College Fjord to Harvard and Yale Glaciers, 20 miles away. College Fjord gashes into the heart of the Chugach Mountains. Harriman named the glaciers along the left of the fjord after East Coast Ivy League women’s colleges and those on the right after men’s colleges.

A pair of southwest-looking photographs, both taken from the same location adjacent to Lamplugh Glacier, show the changes which have occurred at the lower end of Lamplugh’s inlet during the 62 years between August 1941 and September 8, 2003. The 1941 photograph by William O. Field shows the calving terminus of Lamplugh Glacier extending to within 0.5 miles of the photo point.

Icy Bay lives up to its name with an active tidewater glacier often clogging the fjord with icebergs. This remote fjord in Prince William Sound is a special spot for paddlers looking for spectular views of Tiger and Chenega Glacier descending into the sea. Beware of tight ice conditions changing with the tide and strong cold katabatic winds off of the Sargent Icefeild.

One of two tidewater glaciers at the head of Tracy Arm, South Sawyer Glacier extends deep underwater and makes for a very blue iceberg. It is the larger of the two glaciers, and if conditions are good you can come within 1⁄2 mile of the face. Check for mountain goats at the base of the glacier. Just fifty miles southeast of Juneau, this glacier is not one to miss!

Bear Glacier, found in Kenai Fjords National Park, is a tidewater glacier and a popular spot for kayakers, but you can easily see it on a cruise from Seward. With massive icebergs and blue waters, seeing the glacier up close is a thrilling experience. Many people camp on the outer beach near Bear Glacier, and enjoy the glacier views in the background. This is also a great area to check for whales, sea otters, puffins, and other wildlife.

Pedersen Glacier, located in Kenai Fjords National Park, receded throughout the 20th century exposing Pedersen Spit and Pedersen Lagoon. In the 1980s, the lagoon was designated as the Pedersen Lagoon Wildlife Sanctuary, a 1,700-acre sanctuary meant to preserve and protect the area’s wildlife and land. Take a cruise from Seward to see Pedersen Glacier, and the beautiful habitat surrounding it just under 20 miles away.

Both of these photographs were taken from the same location in Nuka Passage, about 6 kilometers (3.7 miles) south of the position of the 1909 terminus of the glacier. The first photograph by D.F. Higgins, is an August 6, 1909 view of the then retreating northern part of the terminus. The absence of any icebergs indicates that by 1909, the glacier was no longer tidewater. When photographed, Yalik Glacier had a gently sloping terminus with… ...more

Billings Glacier is named for British Commodore Joseph Billings who commanded a Russian exploring and surveying expedition in 1791 and ’92. He published no known account of his voyage.

Looking beyond the peninsula you can see snowcapped mountains. Here you have a glimpse into the edge of the Harding Icefield. This icefield is the main feature of the Kenai Fjords National Park. Formed during the ice age some 20,000 years ago, the Harding Icefield is 30 miles wide by 50 miles long and in places presumed to be 3000 – 5000 feet thick. There are at least 38 rivers of ice or glaciers that flow out of the Harding Icefield. From here… ...more

A popular place for cruises and kayaking. You can stop along the shore, pitch a tent and enjoy the solitude and scenic views for a day or two.

Around a hundred years ago, Blackstone Glacier extended all the way out to here. You see rock ridges deposited everywhere by the glacier before it retreated 4 miles to its current location.

Look for three alpine glaciers back in Thumb Cove. Alpine glaciers keep their ice in the alpine region of a mountain and don’t descend to a valley floor or the tidewater’s edge. From the left the three are Prospect, Spoon and Porcupine glaciers. Notice the lovely cabin on the edge of Thumb Cove. The land of the Resurrection Peninsula is divided between state park, national forest and private in-holdings. You will see several private cabins.… ...more

This is your virtual classroom in glaciation. From this vantage point, you can see the three types of Alaska glaciers: piedmont, hanging, and tidewater.

Three north-looking photographs, all taken from about the same offshore location, about 0.5 kilometers (0.3 miles) north of Toboggan Glacier, document significant changes that have occurred during the 103 years between August 20, 1905 and August 22, 2008. An intermediate age photograph shows the glacier on September 4, 2000. The 1905 photograph shows that Toboggan Glacier was thinning and retreating and was surrounded by a large bedrock barren… ...more

Train Access

Spencer Glacier rises 3,500 feet in a stunning, natural ramp from a lake of royal-blue icebergs in the Chugach National Forest just 60 miles south of Anchorage. It’s a family-friendly recreation destination featuring camping, hiking, glacier exploration, nature walks, paddling and sightseeing. Maybe best of all: You have to take a train to get there!

Remote Glaciers

The Knik Glacier snakes out of the Chugach Mountains, tumbling into an iceberg-studded lake that feeds the Knik River. Experience the glacier up close on an ATV tour from Palmer, or a flightseeing trip (with optional landings on or near the glacier) from Anchorage or Palmer. Flights are as short as 90 minutes round-trip, making it one of the most accessible and impressive glaciers from Anchorage.

Three north-looking photographs, all taken from about the same offshore location, about 0.5 kilometers (0.3 miles) north of Toboggan Glacier, document significant changes that have occurred during the 103 years between August 20, 1905 and August 22, 2008. An intermediate age photograph shows the glacier on September 4, 2000. The 1905 photograph shows that Toboggan Glacier was thinning and retreating and was surrounded by a large bedrock barren… ...more

The two included photographs were taken on the northeast side of Wachusett Inlet, Saint Elias Mountains, Alaska. The September 9, 1961 photograph shows the lower reaches of Plateau Glacier, then a tidewater calving valley glacier with parts of its terminus being land based on either side of the fiord. The central part of the terminus is capped with séracs and rises about 35 meters (115 feet) above tidewater. The terminus has a large… ...more

Cross the Tokositna River which marks the southeast corner of Denali National Park. Look for tents or rafts next to the river. While difficult to access — even by bush plane — this area is a prime place for camping, exploring, and to begin a raft trip down the Tokositna River to Talkeetna. Out the left window, you can look south to the Peters & Dutch Hills, an active gold-mining area since the early 1900s. A winter wagon road from Talkeetna… ...more

The Kahiltna Glacier is the longest in the Alaska Range — a 45-mile long river of ice! You’ll cross it 35 miles up it, at an elevation of 5500 feet above sea level. See any dark specs on the surface of the glacier? Those are the climbers and tents of Denali (Mt. McKinley) basecamp! Most climbing expeditions begin here. A base camp manager coordinates communications between climbers and air taxis. During the busy climbing season, there can be… ...more

You enter the Sheldon Amphitheatre, named after a bush pilot who built a viewing hut here on the glacier before it became a national park. You can stay here for $100 a night. It has a wood stove and bunks 6. If you opt for a glacier landing, this is where you’ll likely land. You’ll step out of the plane and onto an ice sheet nearly a mile thick. The scale of the Amphitheatre is hard to fathom. You’ll feel like you can reach and out touch the… ...more

Tebenkof Glacier is named for Mikhail Demitrievich Tebenkof. He governed Alaska from 1845 through 1850 and was the first cartographer to publish charts of the waters of the North Pacific all the way from the Western Aleutians down to Fort Ross, California.

You enter the Great Gorge of the Ruth Glacier — the world’s deepest. The ice is 3700 feet deep, some of it more than a thousand years old. The surrounding walls soar 4000 – 5000 feet above. Were the ice to melt tomorrow, you would witness a spectacle twice as awesome as the Grand Canyon — a gorge a mile wide and nearly two miles high. Watch for climbing camps…These may be the world’s most impressive granite monoliths. You’ll stare in disbelief at… ...more

These three photographs show the significant changes that Tazlina Glacier has undergone in recent years. Read their respective captions for more information.

What you’re able to see of the Muldrow Glacier from the park road is actually just the tip of a 32 mile long river of frozen ice. The Muldrow Glacier is the park’s longest and it is a great example of the power these behemoth ice masses have on the landscape. Much of the lower reaches of the ice are covered in dirt and rocks that have been scoured off of the neighboring mountains on the slow journey from Denali’s (Mt. McKinley’s) flank.… ...more

Stephens Glacier is one of many Alaskan glaciers that is rapidly shrinking. In the photo you can see the retreating terminus of Stephens Glacier with several of its retreating unnamed valley glacier tributaries. The easternmost former tributary lost contact with Stephens Glacier during the later part of the twentieth century. Note the fresh moraine deposits on the valley floor. Photograph taken by Bruce F. Molnia, USGS.

Flying down the medial moraine of the Ruth Glacier is mesmerizing. This 25 – 50 foot high ridge of rock debris looks like an excavation pit that extends for miles down the center of the glacier. Keep on the lookout for deep blue pools of ice melt. Look for lateral moraines on the sides of the glacier and the terminal moraine at the toe of the glacier… You’ll know the terminus of the Ruth when you see it: the contortions of earth and ice resemble… ...more

While not the most spectacular glacier, it nonetheless deserves note because one of the creators of The Alaska App went to Amherst College. We shall say no more. Except one thing: When the Harriman Expedition named the glaciers in College Fjord, they had no idea the insult that would be felt more than a century by Amherst alums cruising Prince William Sound only to discover their alma mater’s namesake glacier is somewhat of a runt.

Look for the historical sign describing the rapid advance of Black Rapids Glacier. During the winter of 1936, this mile-wide, 300-foot-high river of ice advanced an average of 115 feet a day, or over 4 miles, to within a half-mile of the highway. It was dubbed the Galloping Glacier and has been receding ever since.

This is your virtual classroom in glaciation. From this vantage point, you can see the three types of Alaska glaciers: piedmont, hanging, and tidewater.

One hundred and fifty years ago the valley now occupied by the ship facility and correctional center was filled with the ice of Godwin Glacier. If you look just below the 4 mountain peaks to the left side of the valley you can see the ice of Godwin glacier. In the year 1850 this glacier calved icebergs into Resurrection Bay waters. Now a days Godwin glacier is a valley glacier and behind the low hills you see in the foreground Godwin glacier… ...more

To the east is another Ice Age creature known as a rock glacier. Originating in a bowl, or cirque, of the mountain, this undulating tongue of rock fragments moves much like a glacier. But, unlike a glacier, a rock glacier is composed mostly of rocks and has only a core of ice.