Driving the Denali Highway: A Fall Photography Journey

By Daniel Quick

Road trips aren’t measured just by mile markers, but also by memorable moments. The best part isn’t arriving at some destination—it’s all of the wild and beautiful things that happen along the way. That’s particularly true when you travel Alaska’s iconic Highway #8—the Denali Highway.

I came to Alaska as a young man in his early 20s and have traveled to all corners of this great state, from the far western tip of the Aleutian Islands to the North Slope, all parts of the Southeast Panhandle, and most areas in between. Now, in my late 70s, I find myself being continually beckoned, again and again, to one particular byway—the Denali Highway’s 134 miles between Paxson and Cantwell.

The Denali Highway was completed in 1957, and until the opening of the Parks Highway in 1972, it offered the only road access to Denali National Park (known back then as Mount McKinley National Park). As a result, this highly scenic route has been a favorite of many Alaskans over the years. It’s closed during the winter months (you shouldn’t attempt to drive it from October through mid-May) and can get busy in summer. But there’s one prime moment on the calendar when I find myself drawn back: during the fleeting but usually spectacular fall, when an explosion of colors flashes across central Alaska. This display normally begins the last week of August and continues through the second week of September. It’s a short window of opportunity that may end abruptly—amazing one day, but quickly erased the next by a couple of blustery storms. Nevertheless, this time has more often than not afforded me splendor-filled journeys.

Starting in the settlement of Paxson, you quickly climb westward into a high alpine and tundra landscape, paralleling the great Alaska Range just to the south. This land was birthed by up to five separate glacial periods, and numerous reminders of these ancient events remain: eskers, kettle lakes, moraines, and scoured massive peaks. Had you made this trip 10,000 years ago, you would have found much of the landscape covered by ice fields a half-mile thick, while ice-free areas would have supported animals like mammoths, bison, and horses. Today, the terrain plays host to a wide variety of wildlife including porcupine, moose, caribou, beaver, trumpeter swans, fox, and grizzly bear.

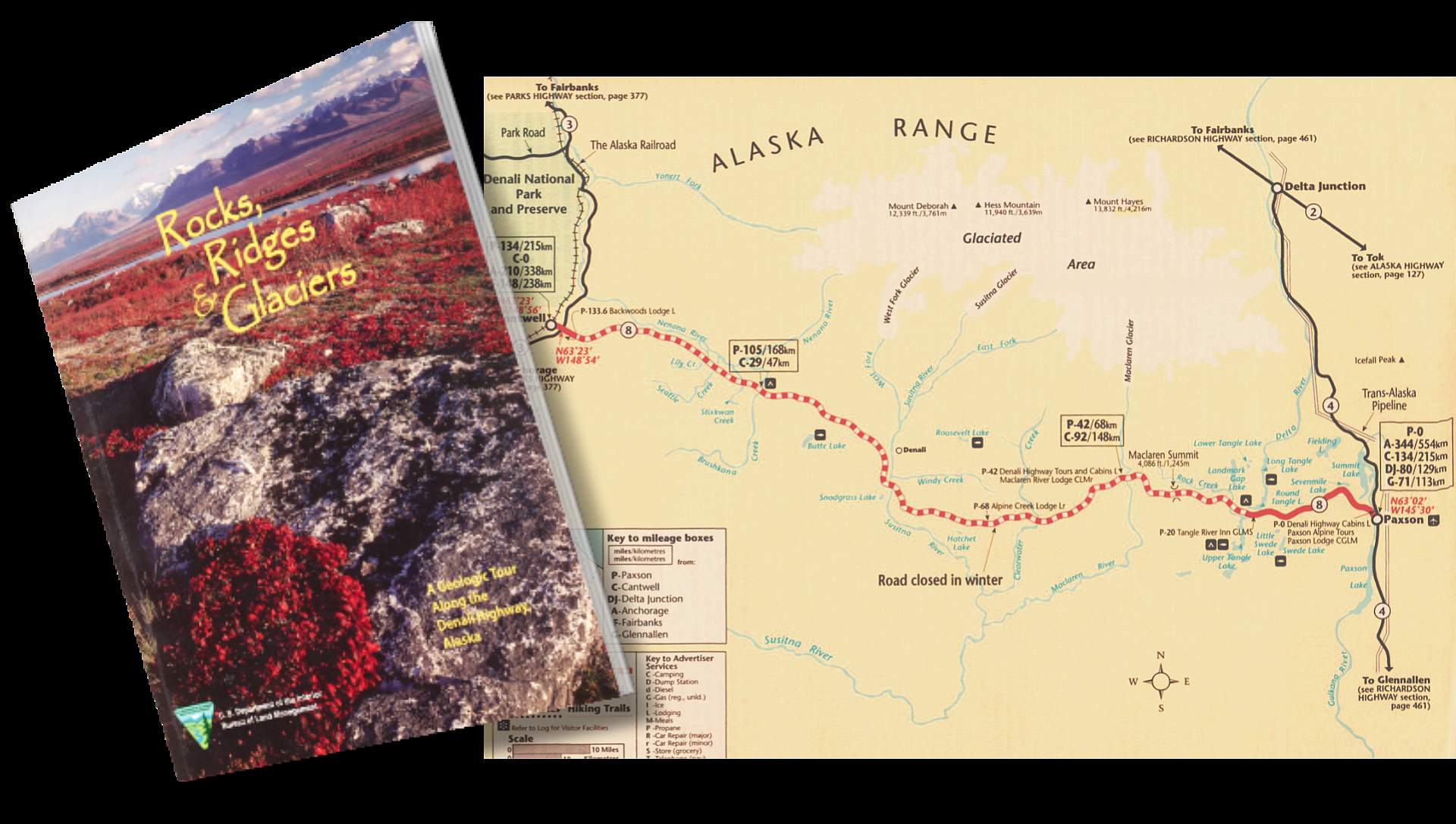

Before making this journey, take the time to study up on the area’s prehistoric foundations and geologic features; it will add immensely to your appreciation of the journey. The best way I know of doing this is to procure the Bureau of Land Management’s book Rocks, Ridges & Glaciers. It features colorful illustrations and articles on geologic features, as well as travel maps, travel tips, and a wonderful, in-depth geologic milepost of the entire Denali Highway. I always carry a copy with me when I make this passage. Periodicals like The Milepost will also prove helpful.

My next bit of advice: slow down. Though the first 21 miles are paved, frost heaves are common. I suggest traveling 25 to 35 mph throughout the trip, especially if you’re in an RV. Slower speeds will protect equipment and spare you a lot of nervous tension. A more modest speed will also allow you to see things you would likely miss at a swifter pace.

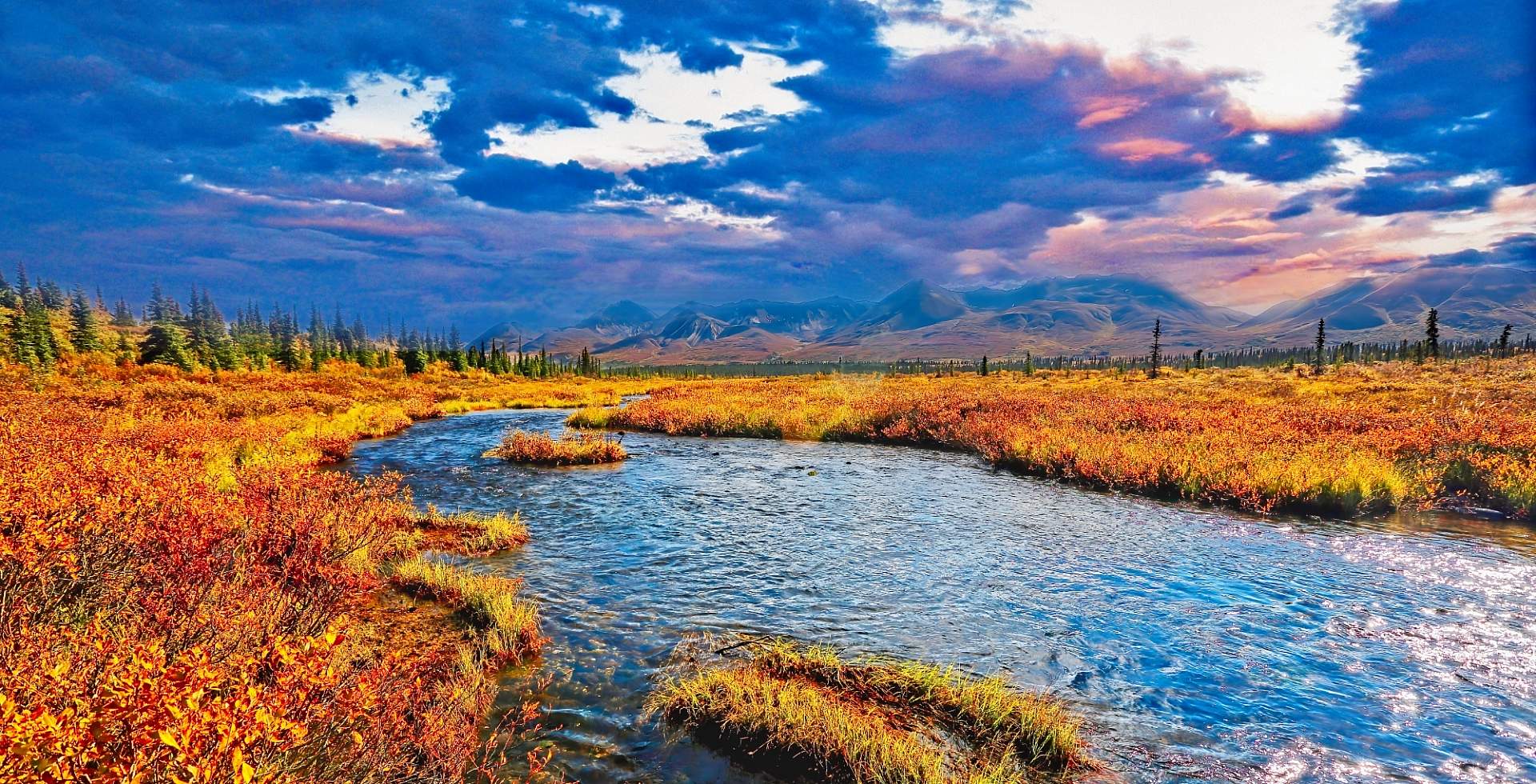

Approximately Mile 2

Case in point: On one year’s journey I was less than four miles out of Paxson when I noticed through the roadside brush, off to the north, a gorgeous scene. It was a little hard to see from the pavement, so I set off on foot. About 30 or 40 yards off the road, I broke through the bushes to witness the spectacle in the photo above, which remains one of my most treasured photo memories to this day. It’s also a great reminder to slow down, enjoy each moment, don’t be afraid to pull over when possible, and get out to take a look around.

As you continue westward, the vegetation quickly changes from spruce forests to alpine tundra. This transition opens up a view to the north of the glacially sculpted Alaskan Range—a virtual wall of mountain peaks stretching 650 miles, from Iliamna Lake far to the southwest to the White River in Canada. Numerous turnouts along this section offer panoramic views of Gulkana Glacier and surrounding peaks, making it another good area to explore on foot. You don’t need a long hike to appreciate it; just walk along some of the small knobs and ridges. You’ll be well rewarded for the effort.

Gulkana Glacier - Approximately Mile 5

I should probably say a word or two about weather. Fall is a dynamic time of year in Alaska, a season of rapid change. Chances are there will be few blue-sky days, but this can work to your advantage. The constantly shifting weather patterns and periodic rain squalls can offer wonderfully dramatic skies. Plus, since the mountain ramparts are to your north and the sun is in the southern half of the sky, you’ll often see rainbows projected against these craggy peaks. It’s possible to capture these spectacles on camera, but that requires some patience. At times, I’ve waited an hour or two for the peek-a-booing sun to light up some of those rain-swept mountains, but the wait has always paid off. I’ve also found that a longer lens helps to pull these magical sights in closer.

Rainbow on the Denali Highway

Next, you’ll cross the Amphitheater Mountains, which extend from Paxson Mountain in the southeast to the Maclaren River Valley, about 30 miles to the northwest. You’ll pass by several small kettle lakes, so-named because of their often rounded shape. As heavy prehistoric ice sheets melted, some land areas remained depressed by the extreme weight of the receding glacier, which were filled in by the watery runoff. You’ll see the surrounding area pockmarked with hummocks, which are also a remnant of stagnant and melting ice.

At Mile 16, you’ll enter the BLM Tangle Lakes Archaeological District. This 226,660-acre cultural site contains some of the earliest and most continuous evidence of human occupation within North America. Hand-fashioned stone tools are evidence that humans inhabited this area beginning about 10,000 years ago. Just remain on designated roads and trails, and be aware that collecting artifacts is illegal. As in many natural areas, leave everything as you found it.

Approximately mile 13 of the Denali Highway

Tangle Lakes BLM Campground - Mile 21.3

The next major stop along the way is the Tangle Lakes, which flow northward along the footprint of an ancient glacier. They form the headwaters of the Delta River, one of only a few rivers that originate south of the Alaska Range yet flow north, all the way to the Bering Sea. This area has long been a favorite destination for campers, boaters, and fishermen. The BLM maintains a nice campground on the shore of Round Tangle Lake, which includes a boat launch. I often spend a few days here enjoying the country, picking berries, and fishing for grayling.

Tangle Lakes Fly Fishing - Mile 21.3

There’s also a nice community here, with opportunities for a warm meal and fellowship with locals. Some years I’ve lingered here a week or so, using the area as a basecamp and branching out on daily photo shoots. And I’m not the only one who finds this area gorgeous: The Tangle Lakes and the upper stretch of the Delta River were designated as part of the National Wild and Scenic River System by Congress in 1980.

Here, the Denali Highway turns from pavement to gravel as it follows the Amphitheater Mountains, which got their unique look from glacial ice originating along the southern flank of the Alaska Range. That ice pushed south, at times covering these 6,000-foot ridges, and carved a four-mile-long, half-mile-wide, U-shaped gap through these peaks, forming the Landmark Gap. Humans used this gap some 10,000 years ago, searching through the high-quality glacial deposits for flint (chert) to help make tools and weapons.

Landmark Gap - Mile 24.5

From here the road steadily climbs upward, winding along a ridge and gaining altitude until it tops out at the Maclaren Summit (elevation 4,086 feet). This is the second-highest highway pass in Alaska and affords a wonderful view of Maclaren Glacier and Mount Hayes (elev. 13,832 feet) to the northwest. Mount Hayes is named after Charles Hayes, an early member of the U.S. Geological Survey who was the first to summit this mountain in 1941.

View of Mount Hayes & Maclaren Glacier - Maclaren Summit - Mile 36.8

Vegetation at this elevation consists of low-growing alpine tundra, and if your journey happens to be in the early summer months, you’ll find an abundance of wildflowers. There’s a good turnout at this summit and a nice 3-mile trail heading north toward the Alaska Range, with good berry picking during the fall season. The State of Alaska Department of Natural Resources recommends this trail for mountain biking and hiking, but no matter what you do, Maclaren Summit is an excellent place to stop and enjoy the view.

Maclaren Summit - Ridge trail heads north toward Alaska Range - Mile 36.8

The Maclaren Glacier snakes its way down from the slopes of Mount Hayes and forms the Maclaren River basin. This great glacier has been the major topographic contributor for much of the Denali Highway. Even the Tangle Lakes, 17 miles to the east, owe their existence to this glacier’s notable past. The Maclaren River flows south from this glacier and joins the Susitna River, which then flows on to the Cook Inlet, just west of Anchorage.

Maclaren River - Mile 43.3

Your journey westward now departs the Tangle Lakes Archaeological District and enters terrain with strong evidence of former glacial activity. At Mile 45, the road passes through a deep notch known as Crazy Notch. This prominent landmark—which has a steep-walled, V-shaped gorge—was formed by an eastward-flowing stream that cut its way through a glacial moraine. What’s interesting is that this stream was deep underneath a glacier at that time, probably as an arm of the Maclaren Glacier, which was merging with some other unnamed glacier.

Crazy Notch - Mile 45.1

As you leave Crazy Notch, you’ll encounter the intersection of two esker sets. An esker is a ridge of sediment deposited by a former stream that tunneled deep under the icy body of a glacier. As it flowed, it built this sediment up enough that when the glacier melted, it left a ridge of rocks, gravel, and sand protruding above the surrounding terrain and following the ancient stream’s path.

Esker trending northwest - Mile 46.1

The road follows the crest of the southwest esker for the next 6 miles, flanked by several unnamed lakes and waterways as it heads toward the Clearwater Mountains.

Numerous lakes and ponds in the area provide a wonderful habitat for a variety of waterfowl and shorebirds. The multi-terraced rolling landscape, which was formed by receding glacial ice, is typical and at times even reminds me of some areas of the great prairies in the lower states.

Approximately mile 55

The tendency here is to drive on by, but many of these hills and small ridges are brilliantly decorated with lichens and vibrant bearberry; they also offer some outstanding berry picking. I’ve been known to satisfy a meal-sized hunger on the top of one of these knobs.

As you continue west, you’ll cross Clearwater Creek at Mile 56. Large turnouts on both sides of the bridge make for informal campsites, with fire pits and a couple picnic tables. Depending on the weather, the roadway can be more challenging as you move closer to the Clearwater Mountains and the Susitna River Valley. You might find times when you end up using both sides of the roadway to avoid potholes, mud boils, and washboard sections. Be safe and consider this section a good stretch to slow down and enjoy the scenery.

The Clearwater Mountains - Mile 70 (approx.)

The Clearwater Mountains were named by prospectors who noticed the streams of clear water, which were distinct from the normally silty waters associated with glacier activity. They’re composed of Triassic-age volcanic basalt, with some flows up to 300-feet thick. Both placer and lode gold are found in old stream channels or along faults and in veins cutting through the rocks; copper-silver lode deposits have also been discovered in the area.

The Susitna River Bridge - Mile 79.2

The Susitna River and valley, which mark a major division in your journey, is an area that I have a deep, personal connection with. In the early 70’s I enjoyed exploring the headwaters of this great river system, all the way to the edge of the mother glaciers of Susitna’s West Fork, Middle Fork, and East Fork. The birthplace of this great river is about 25 miles as the crow flies, upriver from the Denali Highway and deep into the wilderness. I spent weeks traversing these remote areas, which as a bonus helped provide many seasons of food for my growing family. We were perhaps the first to explore the upper reaches of the Susitna by home-built airboat, and I believe it was during those early days, in the upper Susitna wilderness, that the mystique of the Denali Highway was locked firmly into my heart.

The Susitna River northwest of the bridge - Mile 82 (approx.)

Upper Susitna Wilderness - eastern ridge of Middle Fork - Mt Deborah (left) & Mt Hess (right)

Upper Susitna Wilderness - high cirque amphitheater between the West Fork & Middle Fork glaciers

From the Susitna Bridge, the road climbs steadily up a ridge until it breaks out into open country. Watch to your right for a marvelous view of the Alaska Range and the upper Susitna wilderness. There’s a wide pull-off that can double as an overnight camping spot. The view is a classic panorama of central Alaska’s vast tundra country, backdropped by a large number of notable peaks in the Alaska Range. The view to the north (right to left) is of Mount Deborah (13,339’), Mount Hess (11,940’), Mount Hayes (13,832’), Mount Skarland (10,315’), Mount Geist (10,720’), and Mount Giddings (10,180’). Here you can enjoy a campfire and a front-row seat to take in this magnificent wall of ramparts, six of which are over 10,000 feet. The Alaska Range is famous for the spectacular glaciers, some up to 40 miles long, that spring from these peaks. It’s where you’ll find the most, and largest, glaciers in all of Alaska.

Alaska Range view - note the kettle pond in the foreground - Mile 87 (approx.)

Mile 92.3 marks the Continental Divide boundary. Drainage east of this divide flows southward toward the Cook Inlet, via the Susitna River drainage. The waters on the west flow northward into the Nenana and Yukon rivers, eventually reaching the Bering Sea. As already noted, the Tangle Lakes-Delta River drainage is an exception: Though it’s east of this divide, it flows north on its own journey to the Bering Sea.

Near Continental Divide - Mile 92 (approx.) - Mt. Deborah & Mt. Hess in background

As you continue on your westward trek, you’ll enter areas where the vegetation changes from alpine tundra to spruce forest. Along the way are several spots to get some beautiful photos of Mount Debora and Mount Hess. The morning hours provide the best lighting, and often a short hike off the roadway can result in a more pleasing viewpoint.

Mount Deborah - 13,339’ (left) and Mount Hess - 11,940’ (right)

The mixture of spruce forests and tundra landscape continues for several miles; the inclination is to keep moving along without much thought to what lies hidden behind the roadside foliage. I would encourage you to pull over occasionally and explore the terrain just beyond the gravel. It always amazes me how many beautiful places I’ve encountered hidden only a few yards off the main byway. They may be concealed and seldom (if ever) appreciated by humans, but many are quite accessible if you take a little time to locate them.

One of those private, hidden places

At Mile 105 you’ll find the Brushkana Creek and River Campground. You can access the river from both sides of the bridge, and the campground is well maintained by the BLM. There are 22 sites available for both tents and RVs, with fire pits, toilets, and bear-proof litterbins; firewood is available. You’ll also find good grayling fishing here, as well as access to the Brushkana Creek trail (2 miles). This is the second-best camping area on the Denali Highway, second only to Tangle Lakes Campground.

Brushkana Creek and Campground - Mile 105

Another 10 miles brings you to the Nenana River, which natives of times past called both the Tutlut and Nenana. For a short time it was called the Cantwell River, from which the small settlement of Cantwell took its name. In 1898, Lt. J. C. Caster of the U.S. Army reported the river as the “Nanana,” which was then changed to Nenana three years later. It eventually flows into the Tanana River and then on to the Yukon River. Its primary source is the Nenana Glacier, located some 25 miles to the northeast. The Denali Highway parallels the Nenana River through rolling hills most of the way on to the Cantwell Junction.

Photo credit: Yilu Photography, flickr

By this point in the journey the high, glaciated peaks of the Alaska Range have passed from view, covered by surrounding hills. But your journey is about to be rewarded by some stunning views of the Talkeetna Mountains to the south—with some wonderful lakes to reflect their beauty.

Talkeetna mountains reflection

For most of the Denali Highway your eyes have been draw more often than not toward spectacles to the north. Now your attention is drawn to the south. I have often lingered in this area, appreciating this section of country and watching for special moments my camera can capture. All hours of the day have their own charm, but early morning, right at sunrise, offers some of the best opportunities. Great lighting is everything when it comes to good landscape photography, and very early in the day is often the best time to find it.

Sunrise on the Talkeetna Mountains - Mile 130 (approx.)

And now, like a crescendo at the end of a stirring orchestral presentation, the Denali Highway offers its final blessing on your travels. Just before you reach Cantwell, the highway offers a classic view of Alaska’s great Mount Denali, especially at sunrise (and weather-permitting). About 80 percent of Denali’s 20,320-foot elevation rises above the surrounding country; base-to-summit it’s even taller than Mount Everest. Denali, the grandest mountain you will ever see, is a fitting end to a memorable journey through the heart of Alaska.

Sunrise on Mount Denali - Mile 132 (approx.)