Temperate Rainforest

By Elise Lockton

It rains a lot in the temperate rainforest! Why so much rain? The temperate rainforest in Alaska stretches along a 1000-mile long coastal arc from the border of Canada to the island of Kodiak. The mountains along the coast trap moisture-laden clouds moving inland from the ocean and that results in rainfall over 100” in some places. Whether you're exploring the trails around Girdwood or Seward or taking a small ship cruise in Prince William Sound or the Inside Passage, be prepared for moisture.

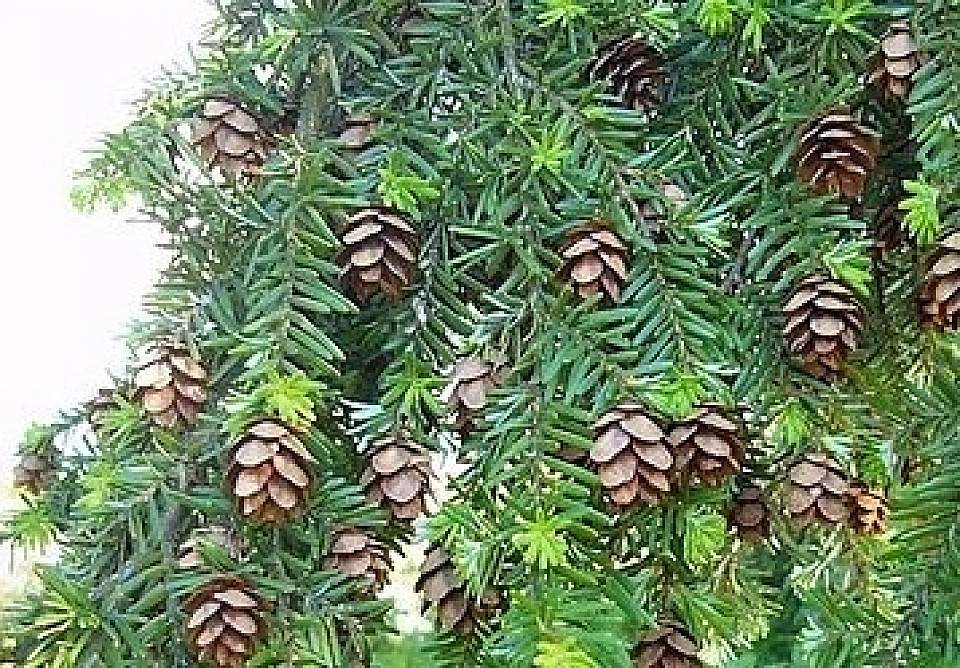

Sitka Spruce

Trees

It hurts to be the Alaska state tree

Sitka spruce can grow up to 200’ and is the world’s tallest spruce. Baskets were woven from long roots by Alaskan natives and the bark eaten fresh or dried into cakes. Because of its high strength to weight ratio it was commonly used for aircraft construction during WWI. Environmentalists had to work hard to find an alternative to Sitka spruce during WWII and with the support of the secretary of the interior they found a substitute. An increase in the supply of aluminum available for aircraft production helped save old growth spruce forests during WWII. As you are walking through the woods look for bark that has potato chip size scales. Another quick way to identify this tree is to grab a branch: the stiff, sharp needles should make you go...ouch!

Western Hemlock. Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons

Western Hemlock

Western Hemlock is the most common tree in the temperate rainforest and prefers to grow in the shade of the spruce. Hemlocks produce lots of small 3/4”cones every year and their rounded needle tips make for a soft touch in comparison to the prickly spruce. Standing on a beach or bow of a boat in Prince William Sound, you can tell hemlocks by their light green foliage and tops that curve downward and appear to begrace fully nodding.

Nurse Log. Photo credit: Leonlngul - Flickr

The nurses of the forest

When a tree falls in the forest it becomes a nursery for the next generation of hemlock and spruce. As these fallen trees slowly decay they provide food and water for young plants. As young trees grow, their roots eventually reach the ground. When the nurse log eventually rots away, a row of trees remains. While you are walking on the Winner Creek Trail in Girdwood see if you can spot a line of trees that sprouted from one of these logs.

Life on the Forest Floor

Everything's bigger in Alaska, except the plants

Dwarf Dogwood

If you see a flower in the forest that resembles the dogwood flower from the eastern U.S. it’s because these two are related. Like many other plants, our species are much smaller in this northern latitude. The 4 big white “petals” of the dwarf dogwood are actually modified leaves and if you look closely inside the white leaves you will find tiny flowers. Later, they become a bunch of reddish-orange berries, edible in small quantities, but not particularly tasty. Another common name for the plant is bunch berry. Look for these around the trails of Girdwood or the Lost Lake Trail in Seward.

Devils Club

The devil dwells on the forest floor

No walk in the forest would be complete without an encounter with the devil. If the scientific name of “horrid” is any suggestion you can assume it’s a plant you want to avoid grabbing. Never has a plant been so endowed with spines than the Devils Club. The leaves are particularly nutritious (rich in protein) and without the spines would be preferred food of moose. Look for a very large maple-like leaf and take a close look for the spines (even on the underside of the leaf). In the fall look for bright red berries in large showy clusters. While not edible to humans the bears love them and quite often you will find evidence of theses berries in their scat on the trail.

Salmonberry. Photo credit: Ruth Hartnup - Flickr

Salmonberry

As you are walking around wet areas in Seward or Girdwood keep your eyes peeled for salmonberry, a 7’ tall shrub that grows in dense thickets. Look for showy 5 petaled pink flowers and large fruits that resemble raspberries. The berries are mixed shades of yellow to scarlet irrespective of ripeness. While edible they area bit on the bland and tart side. Try one and see what you think. Both native and modern Alaskans have consumed this plant. Salmonberry patches were owned by native families or individuals who gathered young stem sprouts in early spring and ate them as a green vegetable. The berries were mixed with fish oil or dried salmon eggs, and were often eaten with salmon. Today Alaskans use the berries in jams and pies.

It's a tangled web they weave

Over 90% of plants around the world depend on mycorrhizal fungi to survive. The fungus wraps around the roots of plants and fungal threads spread throughout the soil drawing water and nutrients into the tree roots. The fungi provide nutrients to the plant in exchange for sugar that the fungi cannot make. Signs to look for of this network are mushrooms growing from the mycorrhizal fungi underground.

Bear fishing for salmon in Brooks Falls. Photo credit: Barbara Du Pont

There's salmon in the trees?

Pacific salmon are a major vector for the transport of marine nutrients to the forest ecosystem. In 8-hours a bear can carry over 40 salmon carcasses into the forest. Those decomposing carcasses feed a form of nitrogen only found in the ocean, to the forest. Spruce and hemlock grow up to three times faster near salmon streams and berry bushes produce more fruit with more seeds. Ptarmigan Creek north of Seward is a good place to see salmon. As you are walking near salmon streams look around for salmon carcasses that have been dragged into the forest by bears.

Light Gaps

Because of the high rainfall in the temperate rainforest, forest fires are not an issue. All forests are dependent on some level of disturbance in order for light to penetrate, allowing the next generation to grow. In this environment it’s the wind and rain that are responsible for that disturbance. Trees are particularly prone to tipping over during the rainy fall season, when soils are saturated, and winds more than 50 miles per hour sweep onshore from the Gulf of Alaska. These fallen trees, create light gaps in the forest and those openings are essential for new trees and other plants to grow. Look for openings in the forest and take note of the young trees growing in this gap.

Animals

Red Squirrel. Photo credit: Wrangell-St.Elias Nat'l Park & Preserve - Flickr

Red Tree Squirrel

One of the most likely animals you will encounter in the forest is the red squirrel. Look for evidence of their cone cuttings on the ground, rocks and stumps. These squirrels are active year-round. Much of their time in the summer is spent with a cone in their forepaws and like corn on the cob they turn the cone, consuming seeds as they go. They cut cones with their teeth and store green cones in a cache. These cone caches can be up to 18’ in diameter and 3’ deep and contain 16,000 cones. These provisions will provide food for them in the winter. The squirrels are particularly territorial during the caching of food so if a squirrel is chattering away at you it may be because you have entered its domain. Look for a mound of cut up cones at the base of a Sitka spruce tree and you just might find yourself a cone cache.

Porcupine. Photo credit: Alaska Wildlife Conservation Center

Quill pig

Porcupines weigh up to 18 pounds and are the 2nd largest rodent in North America next to the beaver. Their scientific name translates into quill pig which seems appropriate for an animal covered in 30,000 pointed hairs. Predators such as wolf or wolverine bite their only unprotected area, the soft and vulnerable un-quilled chest and belly. Porcupines prefer tender alder leaves, violets and marsh marigolds. In the winter they are forced to eat spruce needles and inner bark of hemlock trees which they strip by using their four curved front teeth. As you are exploring the trails around Seward or Girdwood see if you can find evidence of the porcupine’s winter foraging activity and the grooves left by their teeth at the base of hemlock trees.

Stellers Jay. Photo credit: Dick Daniels - Wikimedia

Steller Jay

Steller jays are related to ravens and crows and like their cousins are some of the most intelligent birds in the world. Imitating other birds, like red tailed hawks and bald eagles, they can scare other birds from feeders. One of our year-round residents Steller jays store their food for later consumption. They have a special throat pouch which can store up to 20 seeds. After filling their pouch the birds carry their seeds up to3 miles and bury them one by one. How do they remember where they buried all their seeds? Jays use distinctive rocks, logs, and other features as cues to the locations of their cached food. That mental map allows the bird to return and dig up most of their caches. Amazing!

American Dipper. Photo credit: ADFG - Jamie Karnik

Aquatic songbird

As you walk along the streams in the forest listen for a series of high pitched, melodic chirps and trills that seem to go on for a while. This slate gray bird slightly smaller than a robin, but with a short, stubby tail is the American dipper. The term “dipper” refers to the nearly constant bobbing of the bird’s body and tail. Plunging into raging streams this aquatic bird dives to the bottom looking for insects or snatching small fish or eggs. They have an oil gland above their tail that is 10 times larger than other songbirds of similar size. Using their bills to spread the oil around the feathers, the oil helps to water proof and insulate them. When the dipper comes out of the water you see the water beading off it’s back. It is always fun to catch a glimpse of Alaska’s only songbird that swims in swiftly moving streams.

Pacific Wren. Photo credit: Eleanor Briccetti - Wikimedia

Small bird, big voice

One of the smallest wrens (4.5”) in the United States, the Pacific wren has a short, stubby tail which it usually holds upright. Their amazing song is a series of high pitched, trilling, tumbling notes that last for about 5-10 seconds. During mating season, when a female enters a males territory the male leads the female around to each of several nests he has built. The female then chooses which nest she likes and settles on her mate. Build it and she will come. Listen for these sweet songbirds as you are hiking the Lost Lake Trail in Seward.